May 10, 1908 [Photographie électrique à distance/Long-Distance Wireless Photography]

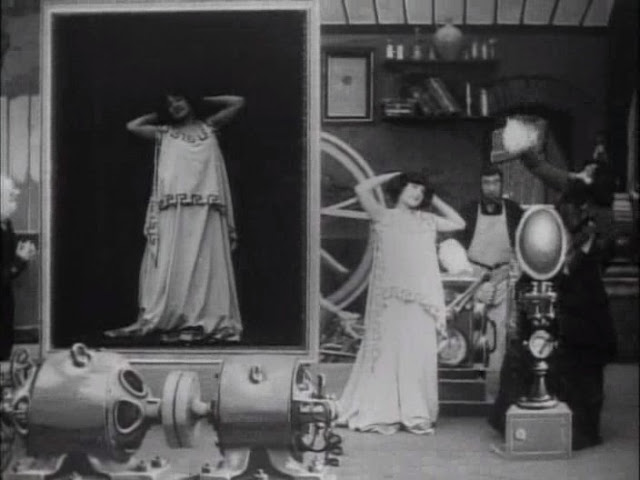

The motion picture seems to be suffering from the nervous urge to assert itself over photography—here, with typical Méliès turnarounds. The inventor (another alchemist, albeit in modern dress, surrounded by gleaming, curving contraptions) entertains the gentleman and his wife—not a typical motion picture audience, to be sure (we are generally a scruffy lot, greatly unwashed)—who are ushered into the electric inner sanctum, where projected photographs come to life—like Melies' playing cards and wall-plastered bills, but here closer in execution to the motion picture projector itself.

The motion picture seems to be suffering from the nervous urge to assert itself over photography—here, with typical Méliès turnarounds. The inventor (another alchemist, albeit in modern dress, surrounded by gleaming, curving contraptions) entertains the gentleman and his wife—not a typical motion picture audience, to be sure (we are generally a scruffy lot, greatly unwashed)—who are ushered into the electric inner sanctum, where projected photographs come to life—like Melies' playing cards and wall-plastered bills, but here closer in execution to the motion picture projector itself.Aha; so Melies is impatient already with his medium, eager to re-invent cinema, a new application/permutation of the image-within-an-image fascination, the still moment animated; the results, however, are less than sublime. The electronic woman's disembodied head has its own grotesque allure—but the man is transformed by the machine into a monkey, insulted by cinema—or put in his place. Méliès always seems the almost-revolutionary, pinching bourgeois noses between the sprockets of his camera—in revelatory fit-ness, to be sure, Darwinian in its mockery. After all, as Junior Rockefeller announced, success in business is simply survival of the fittest. And to undermine such blithe observations, we must hide in the dark—amid the rarebit fiends and thwarted lovers, prankish cupids and college chums—and give the robber barons their due—and just desserts, it appears, the man into monkey, cinematic proof that to survive one must sometimes endure violence—if not to person, then at least pride.

I wonder, sometimes, who is more insulted by such conceits: the man or the ape?

Comments

Post a Comment