July 20, 2010 [Inception]

In Shutter Island earlier this year, Leonardo DiCaprio wasn't sure what he knew, what he remembered, what he could do with it. The movie felt like a Gothic version of Christopher Nolan's Memento—and now as Cobb in Nolan's Inception he lives in dreams again—big-time SF ones this time, yet another grandchild of Philip K. Dick filled with paranoia, split personalities, and breathless plunges down down down where the real life is lived, an underwater Id-land that tells its own truths—and those of others, the ones that play themselves out on the surface. But you have to listen carefully, look into the eyes of your fellow dreamers, and try to figure out who's telling the truth, who's lying—and, most important, which of them is actually you.

Inception has been getting in some trouble with the critics, both professional and online-amateur, for the pliability of its internal rules and the facile nature of its critique of big business. But I think that these elements unpack what's vital about the movie: its assertion that, as Vonnegut says somewhere (Galapagos?), we're headed toward extinction because we've decided that crazy made-up stuff is true, such as that money is important. In Inception, one must be fabulously wealthy to dream inside of one's dreams—unlike Alice, or the King in Alice's dream. They dreamed of dreams for free—but Inception insists the real dreamers are all grown up, and when they dream of flying it's nothing but first class, with hot towels and cold champagne.

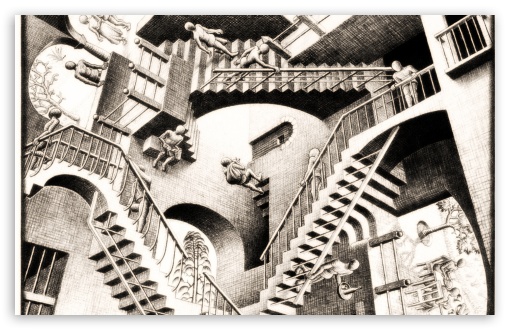

But the movie pushes that one step farther—and over the edge: As we cascade off the bridge, we go past the spinning corridor, through the superspy-secret-lair spy film, and into some kind of ghost town where guilt hides. As in Shutter Island, DiCaprio's character has to press his hand against the unyielding surface of the dream, past the money and privilege that allows one to be an architect of such Escher-spaces, until—well, the surface is unyielding, so one has to become the surface itself, melt into unreality to make the dream come true—or to snap out of it and wake up and be more or less free of crazy made-up stuff.

Inception has been getting in some trouble with the critics, both professional and online-amateur, for the pliability of its internal rules and the facile nature of its critique of big business. But I think that these elements unpack what's vital about the movie: its assertion that, as Vonnegut says somewhere (Galapagos?), we're headed toward extinction because we've decided that crazy made-up stuff is true, such as that money is important. In Inception, one must be fabulously wealthy to dream inside of one's dreams—unlike Alice, or the King in Alice's dream. They dreamed of dreams for free—but Inception insists the real dreamers are all grown up, and when they dream of flying it's nothing but first class, with hot towels and cold champagne.

But the movie pushes that one step farther—and over the edge: As we cascade off the bridge, we go past the spinning corridor, through the superspy-secret-lair spy film, and into some kind of ghost town where guilt hides. As in Shutter Island, DiCaprio's character has to press his hand against the unyielding surface of the dream, past the money and privilege that allows one to be an architect of such Escher-spaces, until—well, the surface is unyielding, so one has to become the surface itself, melt into unreality to make the dream come true—or to snap out of it and wake up and be more or less free of crazy made-up stuff.

Comments

Post a Comment