May 25, 1963 [Pickpocket]

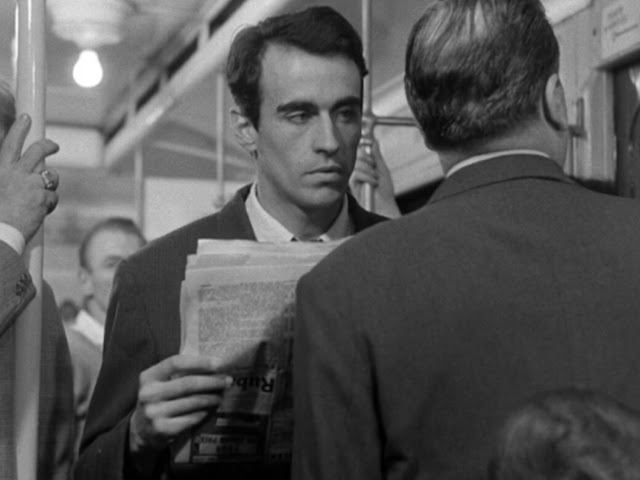

Robert Bresson's Pickpocket, like his A Man Escaped, while cold as a textbook is also fraught with passion—although none is discernible in his heroes' set expressions, the closeups of hands reaching into pockets, scraping prison walls—let alone in their slender frames, efficiently moving through a world set apart—and set against them. At least his escaping man had our sympathies—who wouldn't want a fellow to slip away from Nazis? His pickpocket, though, has no such luck with us—I didn't feel even the sneaky thrill of watching the crook get away with it—oh, there's a little of that, I suppose, but Bresson's thief enjoys it so little (it's simply what he does, and does well) that he isn't in on the fun. We have to be excited for him, worry for him, hope for him. He himself has no hope.

I'm reminded of Bresson's Diary of a Country Priest from about ten years ago. The priest is a saint: filled with resolve but emptied by humility, his flesh mortified, his enemies many. He loves God, but gets nothing in return—except for his saintliness, virtue its own reward (oh yes, that one still haunts me); and Bresson calls those ghosts from the wells into which they had been dropped, the walls in which they had been sealed, the dead-end streets along which they make their weary way. He gathers them like the dead in J'Accuse!, at the end of the first World War, a pale green mass on the open field; and he sympathizes with them—no: He leaves them to themselves, to explain themselves to us. It's our fault if we don't love them, or fear for them (or simply fear them) because they've already done all they can.

I'm reminded of Bresson's Diary of a Country Priest from about ten years ago. The priest is a saint: filled with resolve but emptied by humility, his flesh mortified, his enemies many. He loves God, but gets nothing in return—except for his saintliness, virtue its own reward (oh yes, that one still haunts me); and Bresson calls those ghosts from the wells into which they had been dropped, the walls in which they had been sealed, the dead-end streets along which they make their weary way. He gathers them like the dead in J'Accuse!, at the end of the first World War, a pale green mass on the open field; and he sympathizes with them—no: He leaves them to themselves, to explain themselves to us. It's our fault if we don't love them, or fear for them (or simply fear them) because they've already done all they can.

Comments

Post a Comment